Category: The Hunterian: Art Collections: GLAHM 18224, 18225, 18226, 18227, 18228, 18229

Location: In storage in the Print Room at the Hunterian Art Gallery (may be viewed on appointment)

Physical description: Six Lithograph signed proofs presented in a folio entitled “MUNITION DRAWINGS/ from collection presented to British Museum by his Majesty’s Government/ price £3 3s net/ published by authority of the ministry of munitions/Country Life MCMXVII/ Limited Issue” The six prints included in the contents are:

I. The Giant Slotters

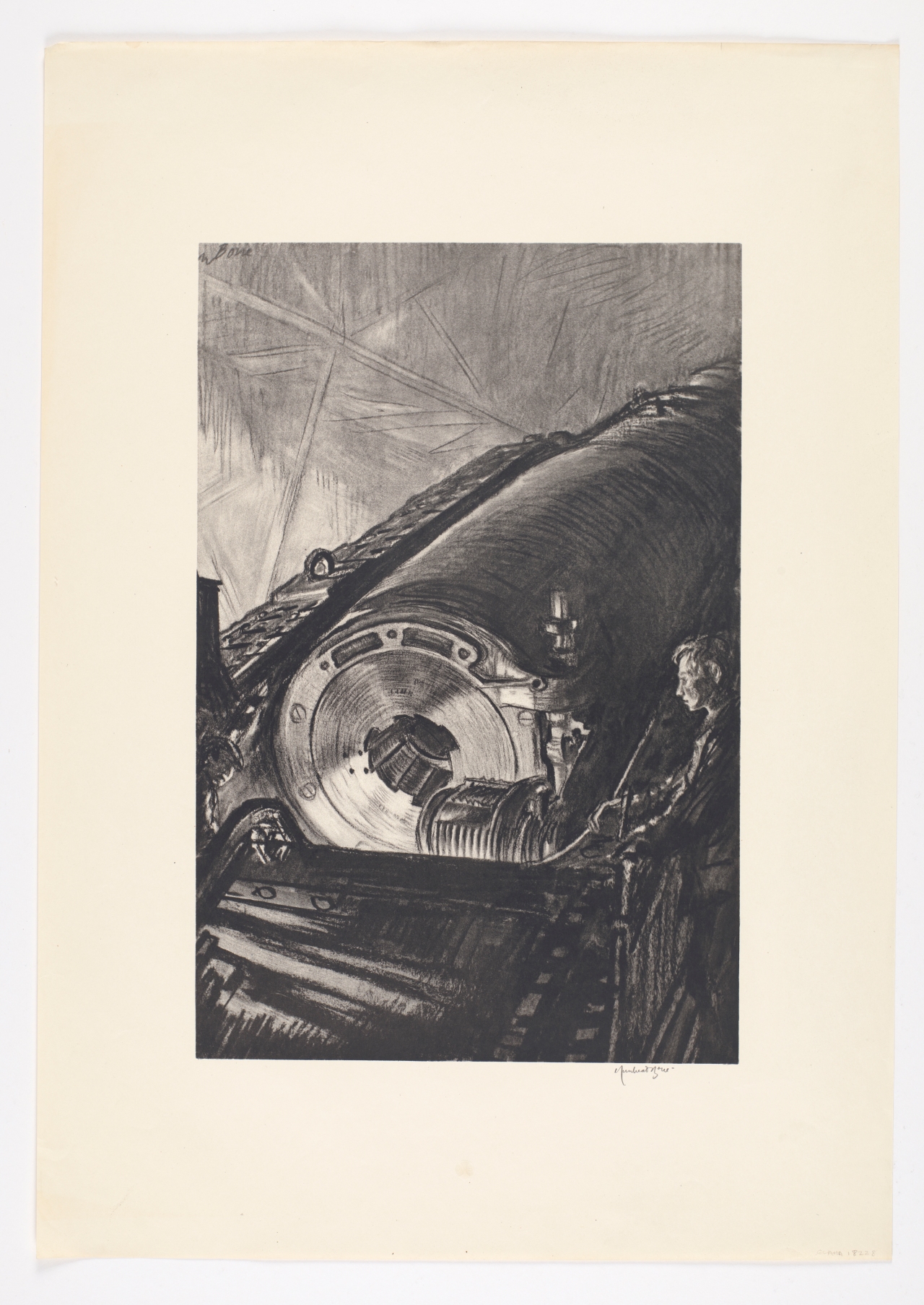

II. Mounting a Great Gun

III. Moving Heavy Gun Tubes

IV. The Night Shift Working on a Great Gun

V. Night Work on the Breech of a Great Gun

VI. A Coring Machine at Work on a big Gun Tube

THE GOVERNMENT’S GOLDEN BOY

In December 1916, Bone’s appointment required him to spend two months in the munition factories of Coventry, Chilwell and Middlesbrough[1] in order to observe and document the machines and men which made up the British workforce. At the time, Bone was the only artist to be officially employed by the British government. He had received national success prior to the war and the works he created during it would provide him with international recognition, particularly in America. His rise in popularity would lead to the rise in his workload. The man once described as having “limitless energy” who “could work undistracted in the most difficult conditions”[2] would suffer a semi-nervous breakdown, less than a year into his appointment due to being overworked and overused.

Muirhead Bone, ‘Munition Drawings: Mounting a Great Gun’, 1917, photo-lithograph, 39.0 x 56.5, ©The Hunterian, University of Glasgow 2013,GLAHA 18225

II. However many large guns may have been turned out by the same men before, a glow of pride is always felt in a gun shop when one more masterpiece like this is ready at last to go out to its work in the field.

Muirhead Bone, ‘Munition Drawings: The Night Shift Working on a Great Gun’, 1917, photo- lithograph, 35.5 x 53.5, ©The Hunterian, University of Glasgow 2013,GLAHA 18227

IV. ‘A scene,’ the artist writes, ‘so romantic in its mingling of grimness and mystery that one thinks with compunction of the long line of romantic artists whose lot it was not to have seen it!’

COUNTRY LIFE MAGAZINE DURING WWI

Prior to the outbreak of WWI Country Life magazine was an unashamedly elitist publication. Its romantic view of Britain’s rural landscape, grand country houses and exclusive country pursuits allowed it to become “the manual of gentrification for the late Victorian and Edwardian middle classes.”[3] The editor during the years 1900- 1925, P.A. Graham resided in the magazine’s editorial office at 20-21 Tavistock Square, London and continued the magazine’s legacy as a “primarily visual rather than literary” publication.[4] This would be the legacy which the outbreak of war and the four, long years which followed, would fail to interrupt.

‘a portrait of the Duchess of Westminster, who has been nursing in her hospital since the beginning of the war.’

In the early stages of the war, the weekly publication often featured daughters and wives of the middle class on its front cover, with a description of how they were contributing to the war effort. Within its pages, further examples of war time contributions were featured, alongside war time political opinions such as articles on; ‘The Opposition to Conscription,’ ‘Field Ambulance on Gallipoli’ and ‘What Cheshire has done for the war.’ Features on animal welfare and how the countryside would fare after the war were constant; ‘Birds and Beasts at the fighting front,’ ‘Homesteads for Heroes’ and ‘Horse Shows in War-time.’ Interestingly for us and in keeping with the magazine’s significance on the visual, Country Life magazine quickly recognised the potential of the works produced by Official War Artists. Bone was one of the first to be featured with his Munition Drawings illustrating an article on the 10th March 1917 and his Grand Fleet lithographs published on May 12th 1917.

But were Bone’s images intended for a wealthy audience? Prior to the war, Bone had made his reputation in London society, but his wartime artworks were believed to be for a very different audience. One view was that “they will have a large scale in England not only to the general public but to the engineering workman public…. And not only will they answer the purposes of propaganda, but they will be a great advantage to British trade after the war by showing in neutral countries the capacities of the great engineering firms of Britain.”[5]The working man, the man that Bone depicts in his images may have been his intended audience, but they would not have been included in the elite, middle-class readership of Country Life magazine. Bone’s imagery would have to reach them through alternative avenues.

A HIGH ART FORM?

Bone’s lithographs were originally presented as limited edition folios, signed by the artist with his embossed monogram featured on each sheet. Country Life magazine were the first publication to then reproduce the works. But Bone’s name and his artworks would transcend the pages of the weekly magazine. “… Approximately 80,000 packets of postcards in two series were printed: ‘Munitions’ and ‘Grand Fleet,’”[6] matchboxes, bookmarks and “other ephemera of the type it was hoped would penetrate down to the ‘lower deck’.”[7] So although once a high art form which would adorn the walls of the Royal Academy, the prints’ role and status changed and evolved. This change was very particular to war-time Britain as the ability of the artwork to communicate and evoke a particular message or emotion to the masses was not restrained by any structures imposed by society or by the art history. The boundaries between high and low art forms became unclear and Bone’s lithographic prints were a key component in this declassification. You can read more on Bone’s First World War prints here.

[1] Meirion and Susie Harries, The War Artists: British Official War Art of the Twentieth Century, (London: N. Joseph in association with the Imperial War Museum and the Tate Gallery, 1983) 10-11

[2] Harries, (1983), 12

[3] Roy Strong, Country Life 1897-1997: The English Arcadia, (London: Country Life Books and Boxtree, 1996), 29.

[4] Strong, (1996), 21.

[5] Susan Malvern, ‘Art, Propaganda and Patronage, an History of the Employment of British War Artists 1916-1919’, unpublished Thesis, Department of History of Art, University of Reading, (Sep, 1981), 150

[6] Malvern, (Sep, 1981), 150

[7] Harries, (1983), 74

Pingback: The Grand Fleet by Muirhead Bone | The University of Glasgow's World War One collections